Physiotherapy

Overview

During an initial assessment a detailed history is taken and recorded to get the background and identify possible contributors to the injury. A physical examination follows which can involve visually and manually inspecting the injury, analysing movement and recording a series of measurements which can be used to measure improvement over time. Based on what the assessment identifies, a treatment plan is devised taking into account what the needs and goals of the client are.

The aim is to create a meaningful reduction in symptoms as quickly as possible. For all conditions an estimate of time frame and required treatment to recovery will be discussed. Subsequent visits will involve a brief reassessment to establish if recovery is continuing and progression of treatment / exercise to safely maximise function. Onwards referral to medical or other practitioners may be recommended if better outcomes can be achieved by other means or if further investigation is required.

Your therapist will collaborate with your referring doctor or specialist, but you do not necessarily need a doctor’s referral unless requested by your insurance company. Contact our clinic to find out more about how you can see a physical therapist today.

Heat/Cold Therapy

Heat and cold therapy are often recommended to help relieve an aching pain that results from muscle or joint damage.

Basic heat therapy, or thermotherapy can involve the use of a hot water bottle, pads that can be heated in a microwave, or a warm bath. For cold therapy, or cryotherapy, a water bottle filled with cold water, a pad cooled in the freezer, or cool water can be used. In some cases, alternating heat and cold may help, as it will greatly increase blood flow to the injury site.

Cold treatment reduces blood flow to an injured area. This slows the rate of inflammation and reduces the risk of swelling and tissue damage. It also numbs sore tissues, acting as a local anesthetic, and slows down the pain messages being transmitted to the brain.

Ice can help treat a swollen and inflamed joint or muscle. It is most effective within 48 hours of an injury.

Rest, ice, compression and elevation (RICE) are part of the standard treatment for sports injuries.

Note that ice should not normally be applied directly to the skin.

Some ways of using cold therapy include:

- a cold compress or a chemical cold pack applied to the inflamed area for 20 minutes, every 4 to 6 hours, for 3 days. Cold compresses are available for purchase online

- immersion or soaking in cold, but not freezing, water

- massaging the area with an ice cube or an ice pack in a circular motion from two to five times a day, for a maximum of 5 minutes, to avoid an ice burn

In the case of an ice massage, ice can be applied directly to the skin, because it does not stay in one place.

Ice Should not be Applied Directly to the Bony Portions of the Spinal Column.

A cold compress can be made by filling a plastic bag with frozen vegetables or ice and wrapping it in a dry cloth.

Cold treatment can help in cases of:

- osteoarthritis

- a recent injury

- gout

- strains

- tendinitis, or irritation in the tendons following activity

A cold mask or wrap around the forehead may help reduce the pain of a migraine.

For osteoarthritis, patients are advised to use an ice massage or apply a cold pad 10 minutes on and 10 minutes off.

Cold is not suitable if:

- there is a risk of cramping, as cold can make this worse

- the person is already cold or the area is already numb

- there is an open wound or blistered skin

- the person has some kind of vascular disease or injury, or sympathetic dysfunction, in which a nerve disorder affects blood flow

- the person is hypersensitive to cold Ice should not be used immediately before activity.

Ice is best used on recent injuries, especially where heat is being generated.

It may be less helpful for back pain, possibly because the injury is not new, or because the problem tissue, if it is inflamed, lies deep beneath other tissues and far from the cold press.

Back pain is often due to increased muscle tension, which can be aggravated by cold treatments.

For back pain, heat treatment might be a better option.

Applying heat to an inflamed area will dilate the blood vessels, promote blood flow, and help sore and tightened muscles relax.

Improved circulation can help eliminate the buildup of lactic acid waste occurs after some types of exercise. Heat is also psychologically reassuring, which can enhance its analgesic properties.

Heat therapy is usually more effective than cold at treating chronic muscle pain or sore joints caused by arthritis.

Types of heat therapy include:

- applying safe heating devices to the area. Many heat products are available for purchase online, including electrical heating pads, hot water bottles, hot compress, or heat wrap.

- soaking the area in a hot bath

- using heated paraffin wax treatment

- medications such as rubs or patches containing capsicum, available for purchase online.

Heat packs can be dry or moist. Dry heat can be applied for up to 8 hours, while moist heat can be applied for 2 hours. Moist heat is believed to act more quickly.

Heat should normally be applied to the area for 20 minutes, up to three times a day, unless otherwise indicated.

Single-use wraps, dry wraps, and patches can sometimes be used continuously for up to 8 hours.

Heat is useful for relieving:

- osteoarthritis

- strains and sprains

- tendonitis, or chronic irritation and stiffness in the tendons

- warming up stiff muscles or tissue before activity

- relieving pain or spasms relating to neck or back injury, including the lower back Applied to the neck, heat may reduce the spasms that lead to headaches.

Heat is not suitable for all injury types. Any injury that is already hot will not benefit from further warming. These include infections, burns, or fresh injuries.

Heat should not be used if:

- the skin is hot, red or inflamed

- the person has dermatitis or an open wound

- the area is numb

- the person may be insensitive to heat due to peripheral neuropathy or a similar condition Ask a doctor first about using heat or cold on a person who has high blood pressure or heart disease. Excessive heat must be avoided.

When cold is applied to the body, the blood vessels contract, vasoconstriction occurs. This means that circulation is reduced, and pain decreases.

Removing the cold causes vasodilation, as the veins expand to overcompensate.

As the blood vessels expand, circulation improves, and the incoming flow of blood brings nutrients to help the injured tissues heal.

Alternating heat and cold can be useful for:

- osteoarthritis

- exercise-induced injury or DOMS

Contrast water therapy (CWT) uses both heat and cold to treat pain. Studies show that it is more effective at reducing EIMD and preventing DOMS than doing nothing.

Heat should not be used on a new injury, an open wound, or if the person is already overheated. The temperature should be comfortable. It should not burn.

Ice should not be used if a person is already cold. Applying ice to tense or stiff muscles in the back or neck may make the pain worse.

Heat and cold treatment may not be suitable for people with diabetic neuropathy or another condition that reduces sensations of hot or cold, such as Raynaud’s syndrome, or if they are very young or old, or have cognitive or communication difficulties.

What is TENS?

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is a therapy that uses low-voltage electrical current for pain relief.

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) is the use of electric current produced by a device to excite the nerves for therapeutic constancies. We will connect the TENS unit to the skin using two or more electrodes. We usually use TENS for nerve related to acute and chronic pain conditions. TENS machines serve by sending stimulating pulses across the surface of the skin and along the nerve strands. The exciting pulses help prevent pain signals from reaching the brain.

TENS devices also further stimulate your body to engender higher levels of its own natural painkillers, known as Endorphins. It is a technique of intermodulation that affects the sensory pathway by changing the impulse, which leads to relief of pain.

- Musculoskeletal pain – Acute postoperative pain and acute post traumatic pain

- Chronic pain: e.g. (rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, etc

- Chronic low back pain

- Painful diabetic neuropathy

- Neuropathic pain

- Visceral pain and dysmenorrhea

- Knee pain

- Sports injuries

- Phantom pain

- Neck pain

- Patients who do not comprehend the physiotherapist’s instructions or who are unable to cooperate

- Avoid the application of the electrodes over the trunk abdomen or pelvis during pregnancy with the exception of the use of TENS for labour pain

- Pacemaker

- Patients who have an allergic response to the electrodes, gel or tape

- Dermatological conditions e.g. dermatitis, eczema

- If there is abnormal skin sensation, the electrodes should be positioned in a site other than this area to ensure effective stimulation

- Electrodes should not be placed over the eyes

- Patients who have epilepsy should be treated at the discretion of the physiotherapist in consultation with the appropriate medical practitioner

- Avoid active epiphyseal regions in children

- The use of abdominal electrodes during labour may interfere with foetal monitoring equipment

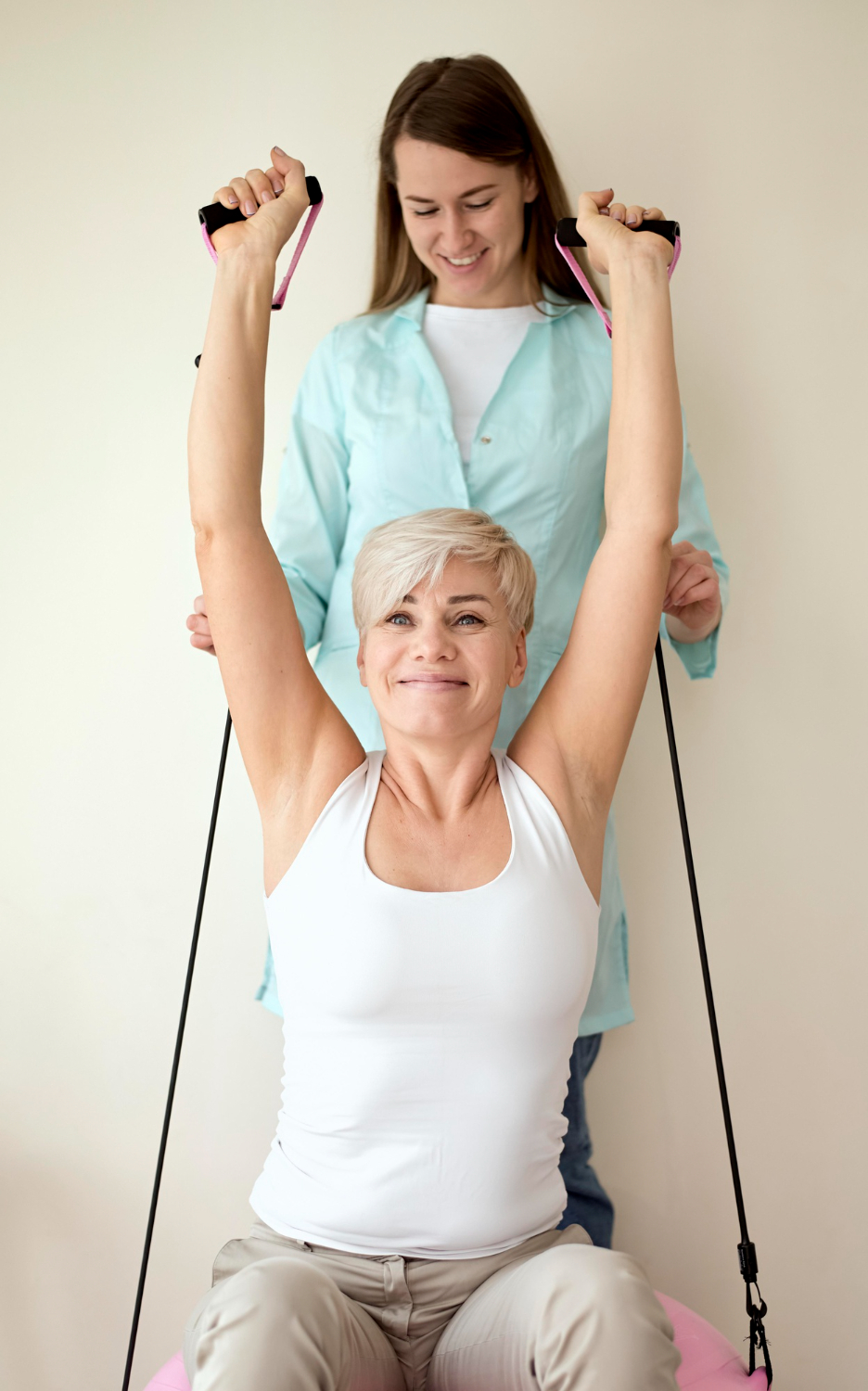

Stretching

Stretching is a form of physical exercise in which a specific muscle or tendon (or muscle group) is deliberately flexed or stretched in order to improve the muscle’s felt elasticity and achieve comfortable muscle tone. The result is a feeling of increased muscle control, flexibility, and range of motion. Stretching is also used therapeutically to alleviate cramps.

In its most basic form, stretching is a natural and instinctive activity; it is performed by humans and many other animals. It can be accompanied by yawning. Stretching often occurs instinctively after waking from sleep, after long periods of inactivity, or after exiting confined spaces and areas.

Increasing flexibility through stretching is one of the basic tenets of physical fitness. It is common for athletes to stretch before (for warming up) and after exercise in an attempt to reduce risk of injury and increase performance.

Stretching can be dangerous when performed incorrectly. There are many techniques for stretching in general, but depending on which muscle group is being stretched, some techniques may be ineffective or detrimental, even to the point of causing hypermobility, instability, or permanent damage to the tendons, ligaments, and muscle fiber. The physiological nature of stretching and theories about the effect of various techniques are therefore subject to heavy inquiry.

Although static stretching is part of some warm-up routines, a study in 2013 indicated that it weakens muscles. For this reason, an active dynamic warm-up is recommended before exercise in place of static stretching.

- Foam Roller

- BOSU

- Stretch Band

- Flex cushion

It’s a good idea, says the American College of Sports Medicine. The ACSM recommends stretching each of the major muscle groups at least two times a week for 60 seconds per exercise.

Staying flexible as you age is a good idea. It helps you move better. For example, regular stretching can help keep your hips and hamstrings flexible later in life.

If your posture or activities are a problem, make it a habit to stretch those muscles regularly. If you have back pain from sitting at a desk all day, stretches that reverse that posture could help.

Your decision to stretch or not to stretch should be based on what you want to achieve. “If the objective is to reduce injury, stretching before exercise is not helpful,” says Dr Shrier. Your time would be better spent by warming up your muscles with light aerobic movements and gradually increasing their intensity.

“If your objective is to increase your range of motion so that you can more easily do the splits, and this is more beneficial than the small loss in force, then you should stretch,” says Dr Shrier.

You should warm up by doing dynamic stretches, which are like your workout but at a lower intensity. A good warm-up before a run could be a brisk walk, walking lunges, leg swings, high steps, or “butt kicks” (slowly jogging forward while kicking toward your rear end).

Start slowly, and gradually ramp up the intensity.

This is a great time to stretch.

“Everyone is more flexible after exercise, because you’ve increased the circulation to those muscles and joints and you’ve been moving them,” Millar says.

If you do static stretches, you’ll get the most benefit from them now.

“After you go for a run or weight-train, you walk around a little to cool down. Then you do some stretching. It’s a nice way to end a workout,”

Yes. It is not a must that you stretch before or after your regular workout. It is simply important that you stretch sometime.

This can be when you wake up, before bed, or during breaks at work.

“Stretching or flexibility should be a part of a regular program,” Millar says.